Welcome to my blog about VOYAGE OF REPRISAL – a nautical fiction novel

MEN WHO GO DOWN TO THE SEA IN SHIPS

I was always amazed how men and women would take to the seas in ships lacking electricity, dependable navigation aids, adequate medical care, or reliable propulsion systems, yet they did. During the Age of Exploration, European sailors dared all the world’s oceans without accurate charts or the ability to calculate longitude. They did so in the time-honored tradition of profit seeking or war making. In doing so, these intrepid mariners and their passengers faced hostile natural elements, disease, malnourishment, mutiny, and enemy guns. The inherent drama of such voyages has inspired many a good sea tale, such as my own.

The setting of this sea adventure novel is 16th century England, the North Atlantic and islands therein, the Caribbean and Windward Islands, the South Atlantic, and the South American littoral. Although most of the story takes place outside Europe, the characters bring their culture with them; they are animated by political, religious, and economic factors long in forming and influenced by events in Western Europe. An understanding of the historical backdrop of Western Europe up to 1585 will help the reader better appreciate the story’s setting.

England is ruled by the last of the Tudor line, the unmarried Queen Elizabeth I. Like her father, Henry VIII, Elizabeth strives to maintain England as an independent Protestant state, although a sizable Catholic minority remains. Ever since Luther, Calvin and Zwingli shaped the Protestant movement earlier in the century, Europe has been divided into two opposing ideological camps with little room for compromise. The imperial Roman Catholic Church, once all-powerful, has lost political and religious control over most of Northern Europe. Pope Sixtus V continues the efforts of his predecessors to mount a counter-reformation aimed at regaining temporal control over these renegade States and stamping out the ‘heresy’ of the Protestant movement. For this purpose, clandestine Jesuits are employed to infiltrate enemy territory and rally the faithful remaining behind. A ‘Holy League’ of powerful Catholic monarchs, led by King Philip II of Spain, tries to coordinate and focus their efforts (monetary, clandestine and military) against the problem.

Compounding the religious dimensions, Northern European states (which happen to be Protestant) also face the imperial designs of an almost overwhelmingly strong Spain. Philip II inherited from his father, the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the thrones of Spain, France-Comte, the Lowlands (modern-day Netherlands and Belgium) and later Portugal (annexed in 1580). The Spanish army is considered the finest in the world. The Spanish Square, or tercio, consists of dense ranks of superbly drilled pikemen backed up by arquebus (early firearm) wielding men on the flanks and armored cavalry. The tercio (or ‘Spanish square’) is considered practically unstoppable. Spain is enormously wealthy from gold and silver bullion extracted from her American possessions. Philip II uses that wealth to finance wars against the renegade Protestant Dutch and the Ottoman Turks. He hopes to stamp out the last bastion of Protestant power in Western Europe – England.

During this time, England only controls half of Great Britain. Scotland is independent and unfriendly. Ireland is nominally controlled but ever ready to rebel from Tudor rule. The loss of her former French possessions has left England and her small population of about 3 million almost marginalized as a nation. Her assets are her mariners and their fighting ships, along with her trade items of broadcloth and tin. She needs markets for these commodities and must fight for the right to trade in an increasingly hostile world.

Philip II held England in his grasp earlier in the century when he married Henry VIII’s daughter, Mary (Bloody Mary) Tudor, who was Catholic. She was Queen of England for a few short years, during which time she tried to bring England back into the Catholic fold. She allied herself with Spain against Spain’s traditional enemy, France. Mary’s policies backfired: France conquered England’s last remaining port towns on the French coast and, despite her oppression, English Protestantism endured. After her death and a short interim under an adolescent King who died young, Elizabeth I assumed the throne in 1558.

Philip II proposes marriage to Elizabeth, as do many other European ruling families, to draw the young queen into his political fold. Elizabeth plays off her suitors one-by-one to bide her time, while building up a secret intelligence agency and a powerful navy. Ever short on cash, Elizabeth begins discreetly financing “armed trading ventures” and out-right piratical forays against Spain’s rich and poorly defended possessions in the Americas. When it finally becomes clear that Elizabeth is a dyed-in-the-wool Protestant who is providing aid and comfort to the rebellious Netherlanders, Pope Sixtus V excommunicates her and Philip plots ways to have her assassinated and replaced with a Catholic claimant to the English throne – Mary Queen of Scots.

A cloak and dagger war ensues; Jesuit agents, renegade English Catholics and Spanish spies collude in plots to kill Elizabeth. English counterspies uncover and foil the plots one by one. Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, is captured in England and imprisoned. English ships begin engaging in a pseudo-war at sea with the Spanish in the Americas. Elizabeth dispatches small armies to the Netherlands while foiling Spanish efforts to do the same in Ireland. Events reach a head in 1585 when Spain formally declares war on England. Philip prepares an Armada to escort the ingenious and ruthless Prince of Parma from the Netherlands to the Thames to crush England once and for all. Elizabeth’s only defense is her renown English galleons manned by her infamous “sea dogs.” Elizabeth’s privateers mount expeditions against Spanish coastal towns and shipping. Some of them are mere piratical expeditions; others spoiling attacks. England fearfully awaits the inevitable assault by a mighty Spanish Armada that aims to ferry the Duke of Parma’s invincible army across the Strait of Dover to English shores. The fate of Protestantism and England’s independence hangs in the balance.

HOW TO ORDER – visit the Kevin J. Glynn Author Page at http://www.amazon.com//author/kevin_j_glynn2021

WHAT IS A GALLEON?

A type of 16th century ship known as a “galleon” is featured in my nautical fiction book Voyage of Reprisal. A galleon was a middling-to-large sized, four-masted sailing vessel without oar propulsion. She had square sails on two forward masts and triangular-shaped lateen sails on two aft masts. This arrangement helped galleons sail well before the wind but also up to 70 degrees into the wind. Although galleons retained fore and stern castles, those superstructures were smaller and more streamlined than that found on other ship types.

Galleons had a narrower width to length ratio (keel length three times breadth) than the round hulled, square-rigged “great ships” (carracks or naos) that were designed primarily as cargo carriers. This allowed the galleon to be swifter (up to eight knots speed) and have more nimble sailing properties while still able to carry a large cargo when used as a merchant vessel. For these reasons, the English favored the galleon for armed trading ventures in prohibited waters claimed by Spain in the New World and in the corsair-infested waters of the Mediterranean.

Galleons had a dedicated gun deck running from bow to stern which allowed them to be heavily armed with laterally firing artillery, unlike most cargo ships and all galleys. When called to fight, galleons were the preeminent warship preferred by Queen Elizabeth’s navy (and her by main adversaries). The English favored the galleon’s stand-off artillery capability and eschewed the old fashion boarding tactics still employed arch enemy Spain, whose galleons and great ships still retained high castles.

The galleon was an outgrowth of the “galleass” which was invented by the Mediterranean Catholic powers to help fight the time-honored galleys of the Ottoman Turks. Unlike a galley (which depended on ramming and bow-mounted artillery to attack an enemy head on), the galleass had both oars and a full rigging of square and lateen sails while employing a laterally firing gun deck to engage a foe attacking from the sides. A galleass could maneuver on oars like a galley but also sail further afield on the open ocean. Six large galleasses performed brilliantly at the 1571 Battle of Lepanto which pitted the navies of Venice and Spain again the Ottoman Empire, giving the Catholic powers a decisive victory. The galleon, though, performed better in the blue waters of the Atlantic because they were more seaworthy than the galleass which became obsolete by the end of the 16th century. The galleon could also fire a greater weight of artillery from the sides.

During the Battle of the Spanish Armada, the Queen ultimately deployed 25 galleons, dozens of supporting craft, and a host of armed merchant vessels (up to 200 total vessels) against a tightly grouped Spanish fleet of 21 older style galleons, 15 large armed merchant ships, a few galleys and galleasses, and a host of supply and transport ships (130 total vessels). By this time, most of the English galleons were rendered even more maneuverable by scaling down their superstructures (especially the forecastle) based on the innovations of master shipwright Matthew Baker.

Although English forces in 1588 initially failed to break up the Spanish Armada’s formation before it could anchor off the French coast and await the Duke of Parma’s army (that was expected to appear on barges to be escorted across the English Channel to England), subsequent naval action dislodged the Spanish from their anchorage and forced them to flee northwards. The invasion of England was thus averted. During this battle, no English ship was sunk and most were only lightly damaged, as opposed to several Spanish ships sunk and considerable damage inflicted on the others due to the close-in English gunfire in the latter stages of the fighting.

Other famous exploits involving English galleons include: the invasion of the Spanish Pacific coast of South America and circumnavigation of the globe by Sir Francis Drake in the Golden Hind; Drake’s raid on Cadiz harbor in 1587; various depredations by English privateers (the Hawkins brothers, Drake, Frobisher, Fenton and others) against Spanish shipping and coastal towns in the New World; and the 12 hour sea battle waged by Richard Grenville in the Revenge against 53 Spanish warships during which time Grenville sank two and heavily damaged 15 other enemy ships before his own ship was captured and he was killed.

The galleon proved itself a formidable asset in the English arsenal during twenty years of open warfare with Spain and was a direct forbear of the famed ships-of-the-line during the classic period of the Age of Sail. For further reading, I suggest The Galleon: The Great Ships of the Armada Era, by Peter Kirsch.

Follow this link to see an excellent graphical representation of how galleon works.

ENGLISH SEA DOGS AND REPRISAL VENTURES

During the reign of Elizabeth I, England struggled to bring her goods to markets controlled by Spain in the New World. Heavily armed English galleons and support ships dared those forbidden waters and forced the locals at gunpoint to trade with them. Later, as relations deteriorated between England and Spain, Elizabeth commissioned privateers to attack Spanish ships and settlements and bring her a share of the plunder to replenish her coffers.

Those who sailed as privateers for the English Crown were granted a “letter of reprisal” so they would not be prosecuted for piracy by the High Court of Admiralty upon their return, so long as they only attacked the nations identified in the letter. The individuals granted these letters were typically sea-captains sailing under joint stock companies financed by private investors.

England’s Admiralty Court appropriated the word reprisal to describe the government-sanctioned pirate raiders sailing out of English ports. The choice of the word “reprisal” was for propaganda purposes as it implied the aggressive actions were retaliations for prior violent acts carried out by the targeted nation. A vessel sailing under the protection of a letter of reprisal was known as a “ship of reprisal,” and the associated private venture was known as a “reprisal venture.” In later centuries, the words “privateer” or “privateering” were used to describe these ships and their activities, because private parties were involved. The term “letter of marque” eventually replaced letter of reprisal.

In addition to furthering her foreign policy aims through privateering, the Queen often gained monetarily because she was due a share of proceeds. The Queen at times lent her own funds and a royal ship or two for reprisal ventures. The privateering voyages generally entailed commerce raiding, but often resulted in the burning, plundering and ransoming of enemy coastal settlements. These were clearly acts of war, prompting the Queen to grant legal cover to her volunteer privateers. Those privateers who were unfortunate enough to get caught by the enemy were treated as pirates and were commonly executed or enslaved, although some wealthy or famous individuals might be ransomed. This was a high-stakes game, and not for the timid nor the risk averse.

Other nations used a similar system. The French called their privateers “corsairs” (derived from a Latin word for a sea route or “course”). French corsairs were issued a “lettre de Course” which was the same as a letter of reprisal. Most of the famous French “pirates” of the early 16th century who plundered Spanish ships and towns in her far-flung empire were technically corsairs, not pirates, since they were acting under the authority of their liege lords in furtherance of France’s perennial wars with Spain.

Queen Elizabeth started commissioning privateers early in her reign, though she always denied it when confronted. Occasionially she temporarily curtailed the practice during periods of delicate diplomacy. A few times she earned spectacular profits. The English seafarers who engaged in privateering were colloquially known as “sea dogs.” Many of these men and their ships participated in the Battle of the Spanish Armada in 1588, supplementing a core force of 21 royal galleons with an additional 180 auxiliary warships. Without the sea dogs, the English could not have mounted an adequate challenge to the Armada.

For more reading on this topic, I recommend an excellent article appearing in Worldhistory.org WORLDHISTORY.ORG – THE SEA DOGS.

ALL PIRACY IS LOCAL

During the reign of Elizabeth I, England was transformed from an insular nation that traded with its immediate neighbors across the Strait of Dover, into a global player seeking new outlets for commercial expansion across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. They key to this change was England’s seafaring heritage, naval innovations, and venture capitalism. England’s major export was woolen cloth, but the old overseas markets were insufficient for this growing domestic industry. England eyed the far-flung settlements of the New World as an outlet, but imperial Spain refused to let English ships trade with her colonies. Nevertheless, joint-stock companies sprung up and armed trading ventures were sent to the Americas to force the locals at gunpoint if necessary to trade with them.

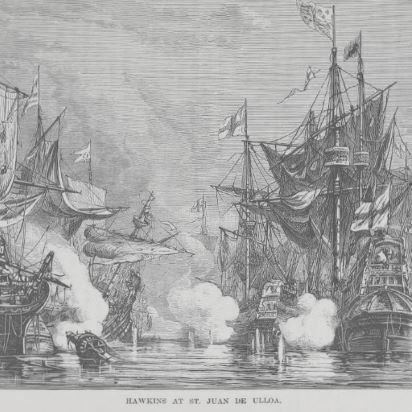

Conflicts with Spanish authorities were inevitable, and several clashes occurred. During the 1568 Battle of San Juan de Ulua, six English merchant ships under John Hawkins (accompanied by a young Francis Drake) were set upon by two royal Spanish galleons and 11 other ships. Only one English vessel escaped from what the English viewed as a treacherous attack.

The ill will caused by such clashes was exacerbated by Elizabeth’s financial and military support to rebellious Dutch forces that were fighting the occupying Spanish in the Netherlands. Efforts by King Phillip II to assassinate Elizabeth and replace her with a more compliant Catholic monarch also heightened tensions. As the geopolitical crisis unfolded, Elizabeth dispatched heavily armed private vessels to plunder Spanish ships and settlements in the New World and bring her back shares of the profits. These “reprisal ventures” were possible because English port towns had robust shipping infrastructures and could provide a large pool of experienced mariners, robustly built ships, and modern nautical equipment.

Many English Channel town’s such as Plymouth and Portsmouth were sources of English privateers during this period, but many smaller towns along the Strait of Dover and up the river Thames contributed as well. When open war broke out and England awaited an onslaught by the Spanish Armada, the new royal dockyard at Chatham (along the river Medway below the mouth of the Thames) hosted the eastern squadron of the English fleet which, after merging with the western squadron at Plymouth, brought 21 royal galleons and 180 private vessels to bear against the 130 ships of the Spanish Armada.

Other small towns along the Foreland, such as Margate, Ramsgate, Dover, and Broadstairs, were nests of smugglers and pirates during the 16th century. For a time, they hosted seaborne Dutch rebels (known as “Sea Beggars”) who were granted safe passage by Queen Elizabeth while harassing Spanish shipping. The Sea Beggars were joined by many English merchant ships and crews from the adjacent coast, who in turn undertook piratical actions against Spanish shipping in the English Channel, Strait of Dover, and lower North Sea.

Small north Kent towns such as Faversham, with its tidal creek snaking through meandering marshlands, exploited proximities to shipping lanes to mount piratical raids and to smuggle ill-gotten gains back home through waterways that were hard for customs officials to police. Official records document how a local sea-captain was charged with piracy in Faversham in the mid-1500s. The most famous Faversham pirate was Jack Ward who worked in local fisheries until he became a privateer in 1588. He participated in multiple attacks on Spanish shipping, even after incoming King James I revoked all “letters of Reprisal” and outlawed attacks on Spain. By 1604 Ward had gone “on the account” (become a pirate), attacking ships of any nation, including England. He eventually operated out of Tunis with the Barbary corsairs where he was known as “Yusuf Reis” or “Yusuf Asfur.”

Adjacent to London was an area of river towns with thriving maritime industries along a stretch of the Thames known as “London Pool.” St. Katherine’s, Limehouse, Wapping, and Rotherhithe were considered official ports of London. Despite the proximity of royal customs officials, smuggling and maritime theft were rampant along the crowded quays. Local maritime industries along the “pool” provisioned and manned many privateering vessels and many unsanctioned pirate vessels.

Oftentimes the distinction between privateers and pirates was blurry. Pirates who were caught and convicted by the Admiralty Court at Marshalsea were hanged to death upon the docks of Wapping. Their bodies were displayed in metal cages along the river’s edge and were inundated for three successive tides. Despite the risk, England’s small port towns provided many “sea dogs” to the Elizabethan naval war machine and to many pirate ventures. My sea-adventure, nautical fiction novels, “Voyage of Reprisal” and “The English Corsair” highlight some of these towns. The two main protagonists hail from Faversham, which is the setting and focus of a chapter. Rotherhithe is also featured, along with “The Ship” tavern on the site of the present-day Mayflower Pub. Broadstairs is a base of operations for a privateer/smuggler character. These books are part of my “Elizabethan Sea Dogs” series.

PIECES OF EIGHT

The Spanish empire in the 16th century was fueled by silver bullion which financed King Philip II’s war machine but attracted hordes of pirates, corsairs, and privateers eager for plunder. The initial plunder of the Aztec and Incan empires by Spain earlier in the century was quickly spent, so a money-starved Spain anxiously sought the source of this wealth. By 1545 they located the fabled “mountain of silver” – Cerro Rico de Potosi – atop a 13,000-foot plateau amidst the Andes mountains in present day Bolivia. Potosi was the site of the largest natural deposit of silver in the world. It would soon account for 60% of the world’s mined silver. Spain started mining the mountain in 1545 using indigenous slave labor and established a mint there in 1574. The mint struck “cob coins” of purified silver that were shipped back to Spain for economic circulation.

The trek homewards from the mines was long and arduous. Llama and mule trains carried satchels of coins down steep valleys to the Pacific Ocean where they were shipped by sea to Panama. More mule trains carried the silver across a narrow isthmus to Nombre de Dios on the Caribbean side. Twice a year, treasure ships transported the silver from Panama across the Atlantic to Spain. Along the way, pirates and privateers occasionally picked off a treasure ship, while hurricanes sank some of the others. Sometimes pirates robbed mule trains crossing the Panama isthmus (Francis Drake in 1573, for instance). Spain began using a convoy system to ensure the treasure made it home so that her creditors would be paid. An overextended Spanish Empire was on annually on the verge of insolvency despite the vast treasure she exacted from the mines of Potosi, so every shipment was vital. A lesser-known and lesser-utilized pathway for transporting silver was down the Rio de la Plata (“river of silver) via Buenos Aires and the south Atlantic to Spain.

Cob coins were crudely rounded pieces of silver shaped like a shield (concave on one side and convex on the other). They were assayed (inspected for purity and weight standards) in Potosi before being transported to Spain. The coins were stamped with a cross on one side and heraldic symbols representing the King of Spain on the other side, along with the Latin spelling for Philip. The letter “P” for the Potosi mint and another letter for the coin series (based on the initial of the assayer overseeing the crop) were also present. When the assayer changed, a new assayer letter was used. In 1586 the assayer letter changed from B to A, for example.

A cob coin containing 25 grams of silver was called a Spanish Dollar. It was worth eight Spanish reales. Cutting the coin into eight pieces (pesos) would yield one reale per piece; hence the Spanish dollar was nicknamed a “piece of eight.” Pieces of eight were made famous in pirate folklore from the 16th to the 18th centuries. In the 16th century, a piece of eight was worth about 5 shillings (a generous weekly wage for a skilled laborer). An English coin known as a “crown” was the equivalent of a Spanish dollar.

A trove of Spanish cob coins minted in 1586 are featured in my nautical fiction novels “Voyage of Reprisal” and its sequel “The English Corsair.”

Leave a comment